Scenes of Harem Life in West European Painting

The discovery of Islamic East to the West European world followed two main paths – one of them was within the process of military or commercial interaction, and subsequently, of studying the basics of social life, language, history and culture. The other way was a creative apprehension of a completely different world with its own laws, customs, special attitude towards life and death, love, feelings, and beauty.

Self-actualization and after all – self-improvement is possible only by perception of another culture. Withdrawal into one’s own world, no matter how “proper” it may seem, results in the self-destruction of this world, only one’s openness to new knowledge and to new experiences, that are at times shocking and damaging to a soul, may provide inspiration and develop one’s culture. This knowledge, despite the drive to conquer new lands and capitalize on wealth, lead the European nations to colonization of vast lands of Asia, Africa, distant oceanic islands and entire continents. Both gleam of arms and alluring jingle of gold, dazzling shining of gems, and, quoting Camoens, "a thirst for storm” attracted people to new horizons and discoveries. Some discoveries generated mercenary value, others awoke political or scientific interest, and others caused a lot of controversy and confusion. And harem became one of the most mysterious and daunting discoveries of Islamic East for the Europeans. The word “harem” is of ancient pre-Islamic origin, it was possibly derived from the Akkadian language, and it is literally interpreted as “hiding place”, “secure part of the house”, “forbidden place”. Harem was and still is completely fenced off from the outside world, an alien’s eye cannot see its mysteries, and all the forbidden and secret things attract and heat the imagination.

Charles-Amedee-Philippe van Loo. “The Sultana Served by Her Eunuchs.” 1773. Jules Cheret Fine Arts Museum, Nice, France Until now, there is no clear attitude in the West to the eastern harem, which of course still does exist today in a slightly modified form. For some people it is an embodiment of savagery and immorality, for others it is the reason to laugh at the “alien” and the “backward”, for the third it is just an echo of Arabian Nights, a beautiful but still a strange world of startling luxury; some people, on the contrary, try to look for some scientific or other kind of explanation, even speaking about the naturalness of such polygamous relationships. In fact, a prototype of harem existed even back in the days among the Arab tribes before the origin of Islam, and the emerging of such type of family was caused by everyday necessity - one wife simply could not cope with the household under the conditions of a nomadic life in the desert, moreover, a lot of men died in continuous conflicts. So Islam was only to legitimize what had already existed and had been a form of survival in the difficult environment, but the number of wives according to the Islamic law was reduced to four, as many as the Prophet Muhammad had. Only in Paradise a man was guaranteed to have an unlimited number of wives and concubines among fragrant flowers, most delicious food, precious fabrics, and exquisite palaces. A harem where there were more than four wives was an epitome of a dream of earthy heaven, feasible only for the elite, who had power and wealth. But was harem like a Paradise for its inmates? Or was it more like slavery and a precious prison with gold-embroidered silks and delicacies? A woman in the Islamic world was, and largely still is, more like a thing – it is notable that the names of wives in the Arab countries could be found in property inventory among furniture, glassware and other household utensils. “They sleep well here whom Allah loved and kept

And treasured in his vineyard fair and fine,

Most lustrous of the Orient pearls that shine,

Which youth found where the waves of passion swept.”

as Adam Mickiewicz wrote in his gloomy sonnet “The Graves of the Harem” Typically the harem women, whether they were wives or concubines, did not live to a great age; they were either killed, with the slightest reason to do it, as a thing should be treated - thrown away when it wears out or just becomes boring, or they died from the exhausting lifestyle that was destructive to women's health and from many diseases. By the way, many of these women became obese with advancing age, and thus were not of interest to a Master anymore, so they became a victim of a slave-eunuch, who suffocated such “worn-out” thing quietly and “humanely” in her sleep. All this is beyond Europeans’ comprehension, however, the harem women often did not care much about this position and they were even pleased with it, being a precious thing, serving their master, bringing pleasure to him – it was their meaning of life, and for many of them it was their happiness. Besides that, they were promised, or rather even guaranteed that they will instantly go to Heaven after death. Harem became a kind of “monastery” where “novices” belonged to her husband in body and soul and with all their lives. They were explained that a great virtue of obedience to the God is achieved through the dedication and serving their husband. The harem women’s consciousness was blunted by the abundance of sweet food, smoking tobacco and sometimes even hashish which is however forbidden by Islam, but it was used in the “education” program for a good harem wife. Idleness and sensuality were nurtured in harem; women were convinced that the God blessed them to ensure “an earthly paradise” for their only master. Women often could not even see other men except for their husband; the richest harems were guarded by ugly eunuchs. The details of harem life that heated the imagination of “enlightened” Europe were first opened to wide European audience by Charles Louis Montesquieu (1689 - 1755) in his “Persian Letters”. On behalf of the Persians traveling through Europe the writer described the life and customs of Islamic East and criticized the vices of contemporary European society steeped in vanity, greed, boasting frivolous, loose morals; he compares two opposite types of culture and tries to be objective, highlighting both shortcomings and praiseworthy aspects. However, even though fantasy and reality find meeting points in fine art, it is the meeting of a colorful rainbow and storm clouds – it is illusory, intangible but it is certainly valid, and no matter that this rainbow fantasy will eventually melt, it will not allow the ordinariness to shed rain and wash out the inspiring mystery and dream... Just like Montesquieu lifted the veil of a harem tent in literature, Charles-Amedee-Philippe van Loo did that in painting. But this “veil” was more like a theatrical drop cloth than a revelation about the real life of harem. In those days of the 18th century “Turkish” masquerades went into fashion – it was there where the ladies of the French society could demonstrate all the luxury of exquisite Eastern fabrics, expensive jewelry, ornate decorative patterns of trendy gizmos, as well as enjoy the amazing game of fantasy. Western secular society created its own “East” which was convenient to escape to from their routine; it was idealized, filled with joy of life, refined luxury, sensuality, and fun. This romantic, theatrical fancy image of the East inspired the creation of tapestries which were fashionable in the interiors of that time, and this image froze in multiple colors of secular paintings. In the picture “The Sultana Served by her Eunuchs” by Van Loo the emerald shades of leaves and pearl satin palette of robes are impressive with their ease and airy mood, the artist praises idle women's lives in the beautiful surroundings and rich palaces. The whole scene is theatrical in nature, and if theater historically originated from ancient pagan rituals, there was a kind of ritual of worshiping beauty and luxury in the 18th century. According to the French artist the harem women would develop their talents – just like the European society women they did fancywork learning from a senior wife of harem. The interiors in Van Loo’s paintings are full of light, they are spacious and open outwards, even though it is strange for the Eastern interior of harem, which is tightly fenced off from the outside world, but it is so close and nice to the imagination of secular Europeans in the age of Enlightenment.

Charles-Amedee-Philippe van Loo. “The Sultana Ordering Tapestries from the Odalisques.” 1773. Museum of Bauty Art

Paintings by Van Loo are the embodiment of high decorative taste, the colors are matched flawlessly, and their exquisite combinations are harmonious, they resemble of the frivolous noise of a masquerade with careful attention to clothes and interior details – they depict a lively interest in the beauty of the world of things, providing delight to the eye and joy to the life. Paintings of Van Loo were often copied on porcelain vases and tapestries. There is a vase depicting the story of Van Loo “The Harem Wife and Her Servants” in the collection of Sevres porcelain of that time.

Charles-Amedee-Philippe van Loo. “The Sultana at her Toilette.” 1783 (detail). National Museum in Versailles.

Works with the same decorative staginess, like the ones of Loo, belong to the brushwork of Jean-Marc Nattier. There is young Mademoiselle de Clermont in his picture of 1733 – with her snow-sugar skin, skillfully exaggerated pearl satin flowing robes shaded by the contrast of the skin of black slaves who served her.

Jean-Marc Nattier. “Mademoiselle de Clermont “en Sultane” 1773. Wallace Collection, London

Jean-Marc Nattier and J.-B. Mass? decorated the Main Gallery in the palace of Versailles, and Nattier’s virtuoso brushwork is filled with masterful and somewhat flippant arrogance of a court painter, who was inspired by scenes of social life inside the splendor of palace walls. However not only the French masters were fond of scenes of harem life. This theme also intrigued many artists from Italy – especially the Venetians, who had long-standing contacts with the East due to the development of navigation and commerce. The Guardi brothers, junior brother Francesco and senior brother Jean Antonio, loved the images of the East very much, especially after becoming familiar with the truly grand work of Jean Baptiste Van Mour, who created the incomparable series of small paintings and sketches depicting costumes, ethnic character types, landscapes and architecture of Islamic peoples of the East. Van Mour had been the French ambassador in Constantinople since 1699, where he became interested in the creation of works which were precious not only from an artistic point of view, but were of undoubted documentary and historical interest. In 1712 all the works of Van Mour were collected into one huge publication named “The Collection of Hundreds of Images of Different Peoples of the Levant”, which became a prominent landmark in the history of Orientalism as an art movement. The collection of Van Mour was a source of images and motifs for the Guardi brothers, who added their own imagination to this experience and created a dazzling brightness and splendor of Eastern luxury on canvas.

Franchesco (or Jean Antonio) Guardi. “Scene in the Harem.” 1742 – 1743. Museum of Art. Dusseldorf

The paintings of the Guardi brothers are imbued with poetry of airborne light touch and trembling game of light-and-dark; and at the same time there is a flexible rhythm inspired by the patterns of Persian carpets. A dream of a carefree life full of sensuality, a convincing sincerity of images in the harem scenes of the Guardi brothers interweaves with the mannered elegance of decorative forms, with unnatural theatricality of postures and gestures.

Jean Antonio Guardi. “The Harem Scene.” 1743. Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Lugano

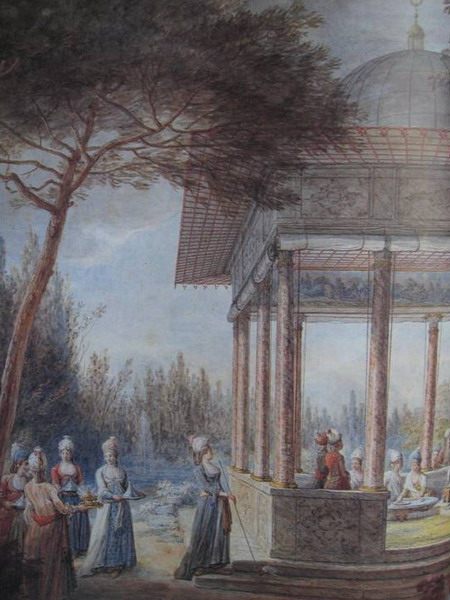

The canvases of Jean-Baptiste Hilaire invite us to enter the gardens of a harem of the Ottoman Empire. Picturesque scenes from everyday life of a harem are unfolding surrounded by nature and exquisite architecture. Hilaire prefers gouache and ink to oil paints due to their ability to convey the sharpness of contours and the haste of movements, with the ability to demonstrate mastery of drawing admiring dynamic lines and vagrancy of figures.

Jean-Baptiste Hilaire. “Harem Scene” (detail) Ink and gouache. 18th century. Paris, Louvre. Graphic Arts Department

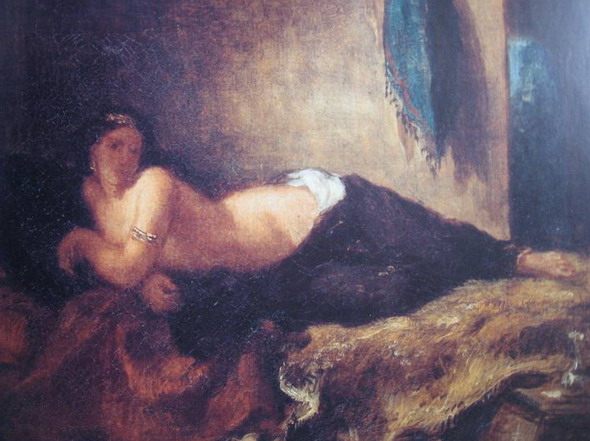

The 18th century in the high secular society of Europe was marked by the blaze of balls and masquerades and by philosophical thoughts about a perfect society under the wise leadership of a “luminous” monarch; the society admired sensuality, elegance and luxury, theatrical art and life itself, which was considered as a magnificent performance in the gorgeous scenery. The 19th century began with the conquest of Egypt, which gave a new impetus to the development of Orientalism and revealed new secrets and mysteries of the East. Art of decoration and architecture were filled with artistic elements shaped as stylized sphinxes, pyramids, and obelisks, new luxury items were brought to the stores of Europe from Egypt, Morocco, and Algeria. The East was associated not only with the fabulous wealth of the court, but also with battles boiling with passion, with courageous warriors, millennial antiquities, splendor of exotic cities, and lives of people under a boiling sun in the vast expanse of the desert. Eugene Delacroix was the artist who managed to reflect to the full the new perception of the East during his era. The most famous of his paintings are the scenes of battles that are stored in the collections of major museums around the world. He did not pass by the theme of harem life. His painting “Women of Algiers” will be quoted by Pablo Picasso in the style of cubism, so it was a kind of a dialogue of eras between the two outstanding masters of painting.

Eugene Delacroix. “Odalisque, Lying on the Couch.” 1846. Paris. Louvre

Eugene Delacroix. “Women of Algiers.” 1834. Paris. Louvre.The 19th century paintings are rich in battle scenes; academic painting has reached unsurpassed heights in this theme. Because battle scenes provided the artists with a very convenient reason to express their mastery of creating multi-figure compositions, their ability to portray the beauty of naked body in expressive motion, to depict the details of the arms, the facial expressions of people with grimaces of pain and terror, with expressions of fear or courage, excellence of the winner or desperate malice of the defeated. Battle scenes achieved popularity due to the fact that they were popular with the nobility; they glorified victories and aroused feelings of pride and self-esteem. But besides the passion of battles, the art cannot do without themes of love and images of women anytime, even at hard times. However some pictures of odalisques created in the first half of the 19th century are somewhat dry and academic, like the one of F. Hayez; many masters also created the images filled with admiration for the exotic beauty.

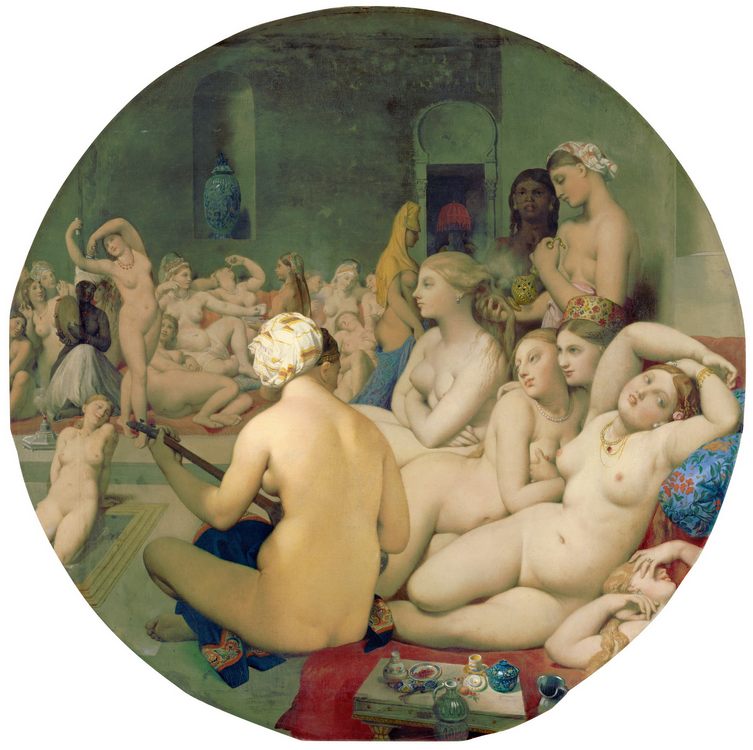

Francesco Hayez. “Odalisque.” 1839. Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan Dominique Ingres was the artist who went down in the history of art as the creator of one of the most attractive works of Orientalism “The Turkish Bath” (1863); he also celebrated the beauty of naked odalisques. He had never been to the East, but eastern poetry, literature, travel notes, as well as his own irrepressible imagination were a constant source of inspiration for him. The artist was impressed by the description of Turkish bath in the letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, which were written during her stay in Constantinople in the first decade of the 19th century.

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. “Odalisque with a Slave.” 1842. Walter’s Art Museum, Baltimore Painting odalisques and harem scenes was a major reason for D. Ingres to admire the beauty of naked female body.

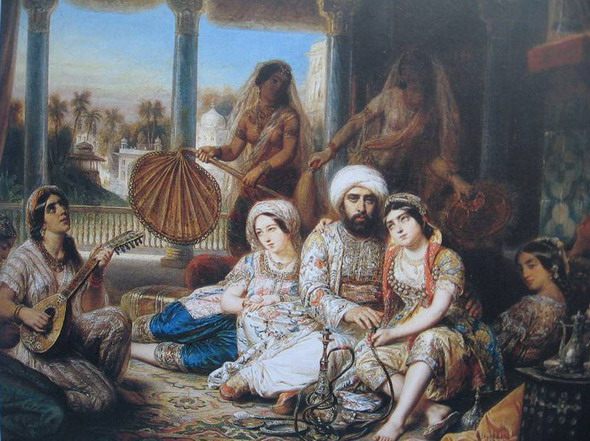

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. “Interior of a Harem.” 1828. Louvre, Paris Now the Europeans had an opportunity to learn much more about harem life than before. This aspect of life of the enemy was not less interesting for the European society, than the secrets of martial art, gold, slaves and lands. Theatrical manner of depicting scenes of harem life was replaced by documentary style, but it was still far from being realistic. European artists idealized this world which was still unexplored and to a large extent closed to them. The worthier is the image of an opponent, the higher is the value of the victory over him. And it's not just about battle scenes. The artists were occupied by the exotic beauty of Eastern women, by their inner peace, their naturalness and sexuality that was cultivated from an early age. In the picture “The Pasha and His Harem” Francois Gabriel Lepaulle admires these women with their languid almond eyes and graceful flowing gestures. The harem wives look like living jewels among the astonishing luxury and abundance of gold embroidered patterns.

Francois Gabriel Lepaulle “The Pasha and His Harem.” Private collection, Paris The image of an Algerian woman in the picture of Tissier is full of peace and concealed sadness – light patches effectively highlight the shimmer of gold and pearls, the glow of tender skin, the dull shine of outwardly calm and dispassionate eyes.

Ange Tissier. “Algerian Woman and Her Slave.” 1860. Paris, Museum of African & Oceania Art The work of Rudolf Ernst stresses the arrogant complacency that was common for the harem women. A woman having taken a bath looks in the mirror with undisguised pleasure, as if once again convinced of her beauty. The face is depicted side-face and the shoulders are turned full face, which reminds of the posing of figures in ancient Egyptian reliefs and emphasizes the peculiar grace and flexibility of Oriental women.

Rudolf Ernst. “After the Bath”. 1889. Private collection in Paris Women of the East that were depicted by the European artists sometimes seem to be too mannered, lusciously soft and simple, or even mysterious, slightly sad and proud, or complacent. This is a very different kind of beauty unlike the European; it excited the imagination and beckoned with its inaccessibility and attractiveness. If the artists of the previous era portrayed contested theatrical scenes from the life of a harem and secular ladies entertaining themselves by playing with the exotic, now the East appears in painting although idealized, but real.

Frederick Goodall. “A New Light in the Harem”. 19th century. Liverpool Art Gallery While the armies raged in battles, artists led their imagination, talent, brushes, and canvases to the conquest of the East. Artists, draftsmen, architects, archaeologists, and travelers, collectors from all over Europe went to Egypt. Frederick Goodall was a British artist who had already acquired considerable fame and good fortune; he traveled to Egypt in 1858 - 1859 searching and finding inspiration in the country that had completely bewitched him. In 1870 he returned to Egypt again where he was traveling through the desert with the wandering Arabs. Then till the end of his life in 1904 he turned to the themes, stories and images that he had seen in Egypt, creating more and more new paintings based on fugitive travel sketches and his bright unforgettable memories. These memories were often colored in the dramatic perception of reality or acquired a symbolic meaning, sometimes he strived for dispassionate actuality or inclined to academic formality, or even on the contrary he was fond of excessive idealization; but, anyway, the artist did not just depict the East, he experienced it, because it had won over his mind and soul. Of course, there is no certainty that he saw a harem. He certainly knew about it, he saw characters of faces, observed manners, gestures, and apparel. His painting «A New Light in the Harem» embodied the real contemplative and measured harem life, the leisurely and idle pastime. The picture is based on the contrast retaining the viewer's eye – the white skin and delicate grace of the wife’s gestures are matched with the black skin of the slave, the light flashings sparkle on it with flair, and with the tenacity and skill of her gestures of her overworked and somewhat rude hands. In addition to the purely external attractiveness the artist introduces some dramatic plot, offering the viewer not only to enjoy the staring at intricate patterns of carpets, fabrics and inlays endlessly, but also to look at facial expressions of the characters and think over their destiny. An attentive viewer would feel the unexpressed sadness behind the outward nonchalance of the wife’s face and at the same time a shade of pride, and the half-closed eyes of the slave betray the barely perceptible pain and envy, because the black slave women, who served in the harem, usually were not allowed to have their own children and were separated from their loved ones, they did not have a chance to create a family. The black slave is holding a dove in her hand, which is largely symbolic, as the dove symbolizes freedom, and her freedom is suppressed, and she feels like a bird clutched in the hands of her slave share. The sadness and loneliness of the slave appear in the eyes of the heroine of the painting by Paul Desiree Trouillebert.

Paul-Desire Trouillebert. “The Harem Servant”. 1874. Museum of Fine Arts, Nice The poetry of lovesickness is praised in the picture of Mariano Fortuny Marsal – a nude odalisque sprawls on the bed and listens to a love song being seemingly unconscious. And the splendor of the Moroccan architecture in the courtyard decorated with carpets on which the beautiful woman is lying, is reflected in the picture by Henri Regnault.

Mariano Fortuny Marsal. “Odalisque”. 1861. Museum of Fine Arts. Barcelona

Henri Regnault. “Patio in Tangiers”. 1869. Gezireh Museum, Cairo The sensuality of Oriental women did not only cause joyful admiration and excite passion, it also evoked thoughts about sinful temptations. The idea of harem seemed although tantalizingly attractive, but totally immoral from the point of view of Christian morality. Therefore, thinking about harem women conveyed the thoughts of a sin and mortally painful temptations. The harem women appear in the image of one of the Temptation of St. Anthony, who had gone into a secluded cave in the picture of D. Morelli, they appear to the hermit as a horrifying vision from under his rough mat.

Domenico Morelli. “The Temptation of St. Anthony”. 1878 (detail). National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome The painting by Cesare Biseo is very unusual in the context of Orientalism; it is made in impressionist style, it depicts the harem wives walking in the park wearing broad white clothes that conceal body and face. The painting reminds of the works by Claude Monet.

Cesare Biseo “The Favorites from the Harem in the Park.” Art Gallery, Piacenza The plots of harem life were not missed by the great Auguste Renoir, who was able to capture an elusive moment in his colors and convey the subtle shades of mood and awe of bright colors in the variety of shades and highlights.

Auguste Renoir. “Odalisque from Algeria”. (detail) 1870. National Gallery of Fine Art, Washington

Auguste Renoir. “Parisian Women Dressed as Algerians (A Harem in Montmartre)” 1872. Collection Matsukata, Tokyo Paul-Louis Bouchard reproduces the feeling of vortex dance motion and mesmerizing melodies, as if they were voicing the ornate weave of the Arabic script and elegant patterns.

Paul-Louis Bouchard. “Egyptian Dancing Girls.” Paris, Musee d'Orsay Along with the idealization and admiration, curiosity and wonder many works of the artists of the 19th century are filled with the awareness of servile position of such women and the feeling of pity on them.

Jean Jules Antoine Lecomte du Nouy. “The White Slave.” 1888. Museum of Fine Arts, Nants By the early 20th century some works contain the disillusionment of the «Oriental fairytale»; a woman smoking hookah depicted by Emile Bernard looks absolutely miserable, frustrated, she is rough and not so attractive. The artist traveled through the Middle East from 1893 to 1904.

Emile Bernard. “The Smoking Hashish.” 1900. Musee d'Orsay, Paris The women on the banks of the Nile in the picture of Bernard are full of sadness and fatigue under the burden of hard work. The artist seems to echo the words of a fictional poet Alvaro de Campos (created by F. Pessoa), “The light on the road without stop is full of grief – The East bores me, like a mat, which one folds up – and the bright colors are gone.”

Emile Bernard. “Women on the Banks of the Nile.” (detail). 1898 – 1900. Museum of Fine Arts, Lille Many artists of the first half of the 20th century again, like in the 18th century, demonstrate the East as being theatrical, as a kind of place, be it real or imagined, to which one can escape and hide from the boring civilization. H. Matisse visited Morocco and Algeria more than once, he was inspired by decorativeness of colors and flatness of patterns, which is so close to his artistic style.

So, the reflection of the harem life scenes in the Western painting is both a sensitive observation, as if an alien mystery that was shamelessly peeped at with a curious eye and a dream of some other dream – a dream of a European about the luxury of the East, a dream of Paradise, of beauty that is strange and inaccessible to outsiders, and finally it means sweet and painful thoughts about freedom and captivity, love and hate, passion and longing. Yana Naumovna Lukashevskaya, fine art expert, independent art critic and exhibition curator for fineartlib.info

|

It seems that the image of a woman in a harem is well-known and unambiguous, but the presented pictures show her in different moments, in different ways. It's very unusual to see the heroines of "The Favorites from the Harem in the Park" by Cesare Biseo - the images of Oriental women are painted in a rather western, impressionistic manner. And, on the contrary, the work "The Sultana" of Ferdinand Roybet is very oriental - both in colors, and in patterns of clothes and interiors. The painting [Expand]

1